Among the World War I memorabilia on display from the collections of Beth Ries and Peter Harvell were fearsome hand-to-hand weapons but also “trench art” created by soldiers from spent shell casings and other materials.

One hundred years to the day after the World War I armistice was signed, voices rose in song and the memories of the three Lincoln servicemen killed in World War I were honored on November 11.

More than 100 attendees filled Bemis Hall for the Veterans Day event in a parallel to a celebration held in the same exact spot (Bemis Hall) in May 1919. The singers and speakers were different, but the songs sung and the servicemen honored were the same, culminating with the presentation of Massachusetts Medal of Liberty to four descendants of one of those who died.

In 1917 when the United States entered the way, Lincoln had 1,200 residents. Of those, 32 percent were foreign-born and thus not eligible to serve in the military, but 72—or about about 40 percent—of the other men in town joined the service.

“For most who served, the war was brief but intense,” said Donald Hafner, an expert in international politics and American foreign policy.

Among the Lincoln veterans who survived were Bertram Anderson, a bugler with the 7th Cavalry who fought as part of Canadian and British forces, served in a balloon squadron, and was the white commanding officer of an all-black engineering service battalion. Another, Ralph Bamforth, spent two years on a training battleship on the East Coast, where German submarines sank 32 Allied ships in the summer of 1918. A third, Thomas Eliot Benner, volunteered to be a long-range bomber pilot—a job where the life expectancy was 90 days for those who survived the training, Hafner said.

One of the Lincolnites who did not return was John Farrar Giles, who enlisted as age 20 even though no one under 21 was subject to the draft. He was killed in battle during a German artillery barrage in Seicheprey, France. Another from Lincoln, Pvt. Wilder Marston, was wounded in the Second Battle of the Marne in July 2018 and later died of his wounds in an Army hospital—one of 12,000 American dead and wounded in the battle.

A third Lincoln resident in the service, Charles A. Cunnert, died in an army hospital of scarlet fever. The son of German immigrants, he joined army before the United States declared war and served on the Mexican border under Gen. John “Black Jack” Pershing fighting raids by Mexican revolutionary general Pancho Villa.

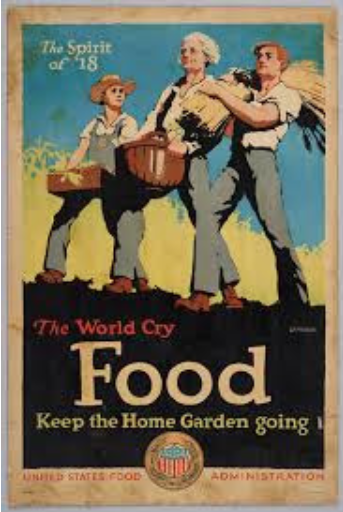

On the home front, in addition to stocking first aid kits and knitting items for servicemen, women moved into traditionally male roles, Palmer Faran said. Women took up farming and also worked as telephone operators, factory workers, and stenographers. This shift in roles and attitudes played a major role in passage of the 19th Amendment giving women the right to vote in time for the 1920 election.

Lincoln women certainly did their part as well, BJ Sheff said. Louise Derby was one of many who enlisted as yeomen in the U.S. Navy to free up the male sailors for combat duty. Helen Osborn Storrow offered up her summer house on Baker Bridge Road (now the Carroll School) as a convalescent home for injured soldiers, and Ruth Alden Wheeler volunteered for overseas duty with the Red Cross in France and later Switzerland after the war, where her duties included writing letters home for soldiers and searching among the wounded for those reported missing.

Descendants of John Farrar Giles surrounded by Lincoln Veterans Officer Peter Harvell (far left) and Sen . Michael Barrett (far right) during the medal ceremony.

“There are many divisions that, not for the first time, that seem to split us as American citizens… but the one institution that survives to unite us is the idea of military service… despite misgivings about particular wars,” said Mass. Rep. Michael Barrett before the medal presentation to Giles’s descendants. “For individual servicepeople, we stand with profound respect.”

Seventeen veterans were just elected as new members of Congress from both parties, Barrett noted. “There’s something on which to build back a sense of commonality and sense of shared commitment.”