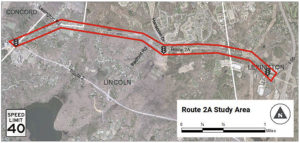

Plans are being finalized for repaving and making other improvements to Route 2A between I-95 on Lexington and Crosby’s Corner in Concord, but work won’t start for another 18 months or so. Meanwhile, Minute Man National Historical Park (MMNHP) is also looking into a bus shuttle service serving the three towns.

Plans are being finalized for repaving and making other improvements to Route 2A between I-95 on Lexington and Crosby’s Corner in Concord, but work won’t start for another 18 months or so. Meanwhile, Minute Man National Historical Park (MMNHP) is also looking into a bus shuttle service serving the three towns.

The Massachusetts Department of Transportation (MassDOT) is designing the project based on a study by Toole Design Group. At a stakeholders’ meeting in October 2020, the company presented ideas for improving safety along the stretch of road, including crosswalks, traffic islands, and possible even a small rotary at the intersection with Old Massachusetts Avenue. Widening the road to provide dedicated bike lanes and pedestrian shoulders was considered, though this would increase vehicle speeds and damage historic stone walls.

Traffic-calming elements at intersections will be installed as part of the repaving project that is expected to start in fall 2022 and run until spring 2024. More involved changes to the roadway, including construction for pedestrian accommodations at the proposed roadway crossings, are being contemplated as part of a second phase, according to Kristen Pennucci, Communications Director for MassDOT. That work, which will require more detailed design development and additional stakeholder input, would not take place until after 2025 to avoid conflicting with MMNHP’s Battle Road 250th anniversary celebration events.

Eighty percent of the costs will be funded by the Federal Highway Administration, with the remaining 20 percent coming from the state.

“We have been in close communication with stakeholder groups as the design has progressed and we welcome their input,” said Pennucci. From Lincoln, those groups include the Roadway and Traffic Committee and the Bicycle and Pedestrian Advisory Committee. MMNHP and the regional Battle Road Scenic Byway Committee will also offer input, and the general public will be able to comment at a meeting to be scheduled after the first design submission for the repaving project in fall 2020.

The project does not include finishing the sidewalk on Bedford Road from its current end in the vicinity of 190 Bedford Road up to its intersection with Route 2A. “Since Bedford Road falls under local jurisdiction, MassDOT anticipates that this sidewalk construction work would be undertaken by the Town of Lincoln as a separate action,” Pennucci said.

The Route 2A bridge over I-95 is also due for replacement and that work will likely be federally funded, but there’s no timeline for that project yet, she said.

Shuttle study

Within a month or so, consultants are expected to finish a feasibility study on creating a shuttle service that would jointly serve the park and towns that the park runs through. The goal is to alleviate traffic and parking congestion along Route 2A and in downtown Concord especially during commute times, while improving the park visitor experience. Congestion is only expected to increase as development in the area continues and park visitation goes up around the time of the 250th anniversary of the “shot heard ’round the world.”

Concord and Lexington already have town-sponsored shuttle services to MMNHP. The towns have indicated interest in jointly sponsoring a service, inspiring the feasibility study by the Volpe National Transportation Systems Center. Volpe will develop up to three shuttle service scenarios that will include estimates on parking capacities, costs and ridership as well as possible routes.

In an unrelated development, the Battle Road Scenic Byway portion of Route 2A was recently designated as an All-American Road by the U.S. Department of Transportation. Both designations recognize roads with archeological, cultural, historic, natural, recreational and/or scenic qualities and are intended to promote tourism and local business, but they do not offer any federal funding or special protections.