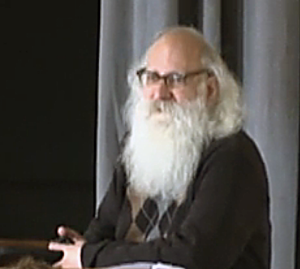

Town Historian Jack MacLean was recently honored with a proclamation of appreciation by the Select Board after he received the Star Award for “long-term volunteer contributions to public history” from the Massachusetts History Alliance.

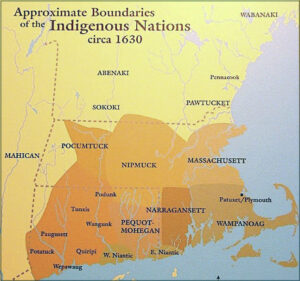

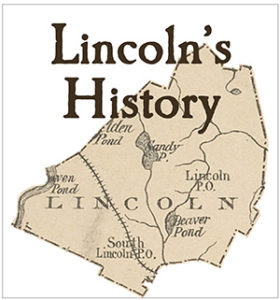

MacLean, who was born and raised in Lincoln, began putting more time into researching the town’s history in the early 1980s and eventually became “the authoritative resource for any and all of the many inquiries directed his way about the town’s storied past,” according to the proclamation, which was based on a nomination submitted by the Lincoln Town Archives. He became the official town historian in 2016 and is author of A Rich Harvest: The History, Buildings, and People of Lincoln, Massachusetts.

“For almost 40 years, Jack has willingly shared his encyclopedic knowledge of, and thoughtful insights about, local history with all who seek to know and understand,” the documents reads. “Jack reminds us that, every day, the legacy of the past shapes the town we currently inhabit, and can help inform our choices about the kind of community we want to leave to future generations.”