Lincoln resident Ron Rosenbaum photographed these turkeys helping themselves to some much-needed water.

The drought we’re experiencing is causing brown lawns and dry land where water used to be—but it’s no picnic for the area’s plants and animals either, as three local experts explained at a presentation titled “Brown is the New Green.”

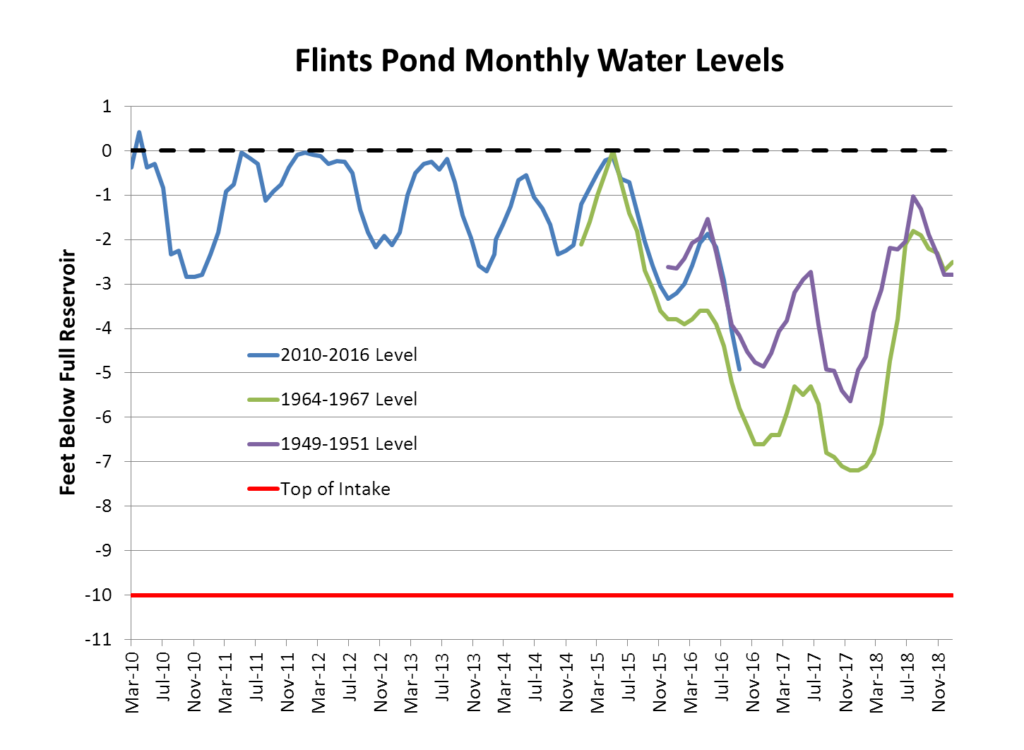

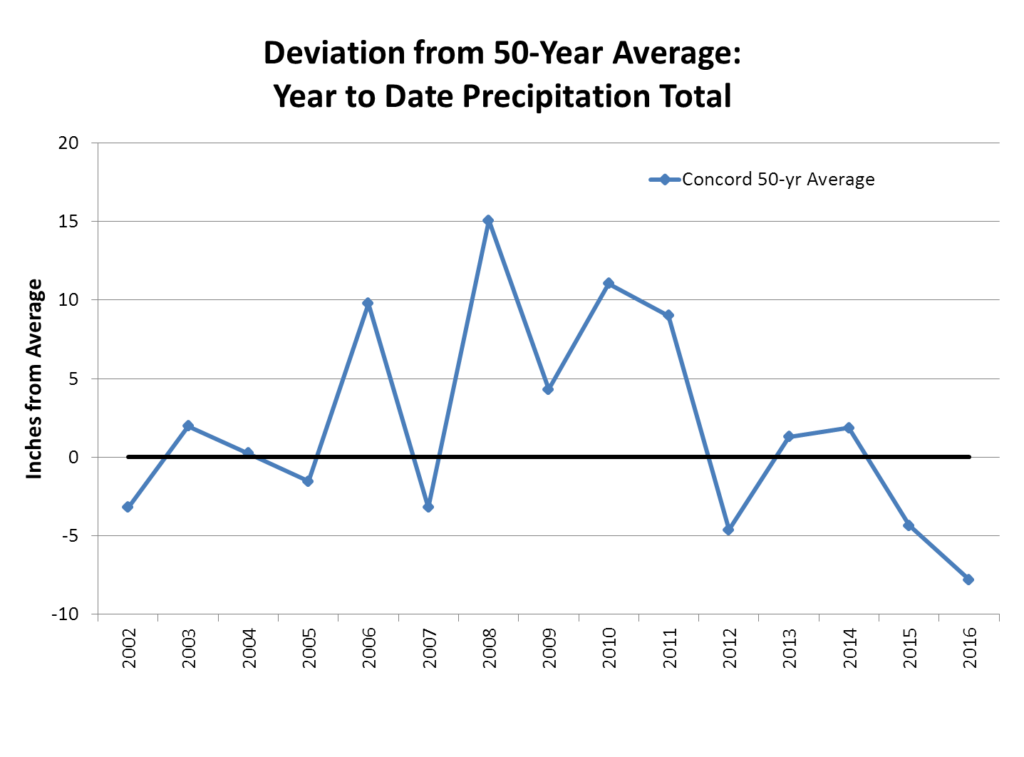

Residents at the well-attended September 21 event in Bemis Hall learned that this isn’t the worst drought in recent history—yet. The worst droughts in Lincoln in the last few decades were in 1949-51 and 1964-67, said Greg Woods, Superintendent of the Lincoln Water Department.

“We’ve been at this level before,” said Woods, showing old photos of Flint’s Pond at low levels. However, the coming of winter snows doesn’t necessarily mean things will go back to normal right away. “We have to prepare for the worst and hope we have a very wet winter and spring,” he said.

Water levels in Flint’s Pond, with different colored lines for 2010-16 and two earlier droughts, 1949-1951 and 1964-1967.

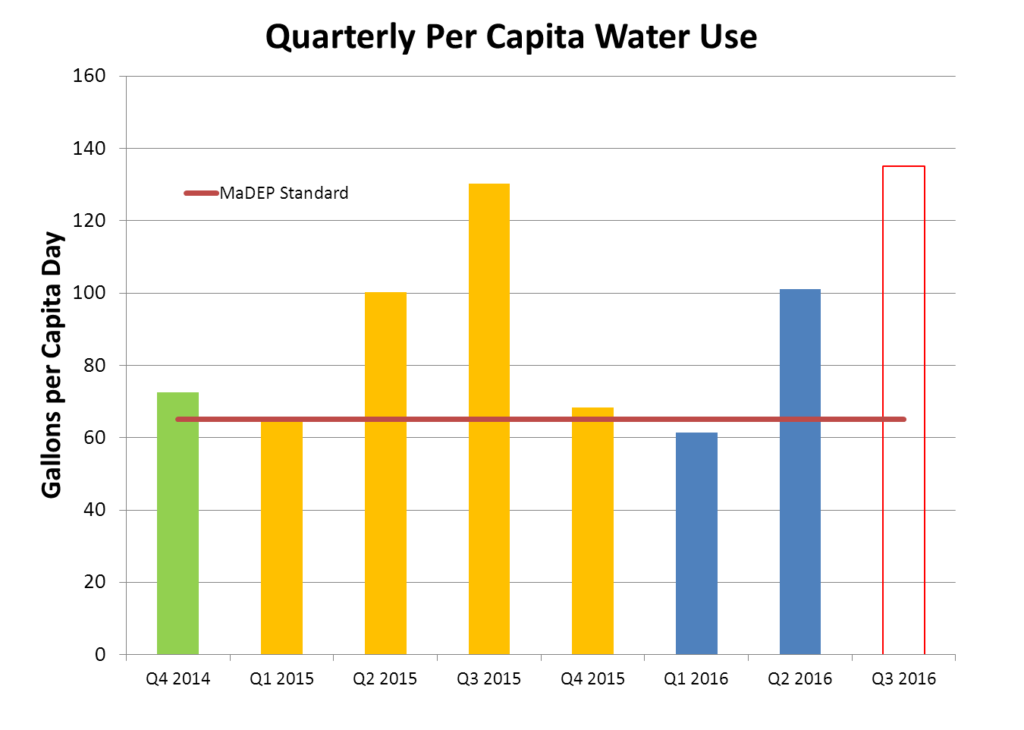

Quarterly per-capita water usage in Lincoln, with a red line showing the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection standard.

Lincoln residents have used about 10 million more gallons of public water this summer than the average for previous summers, said Woods as he showed a series of charts on water consumption and precipitation. Usage has declined somewhat since the mandatory outdoor watering ban went into effect on August 21, but residents are still using far more than the state target of 65 gallons per person per day. The town meets the goal from October to March, but it goes up to about 130 gallons per person per day during growing season, Woods said.

The biggest culprits in outdoor watering are traditional sprinklers, which spread water in places where it isn’t needed and also result in water loss due to evaporation, Woods said. Soaker hoses minimize evaporation loss but still use about a gallon of water per minute, “so you’re still going to use hundreds or thousands of gallons,” he said. The gold standard today is a drip irrigation system, he added

Effects on flora and fauna

The current drought should be viewed in the context of a warming climate, according to Richard Primack, professor of biology at Boston University. “It’s very clear we’re in a warming trend associated with global warming and the urbanization of Boston,” he said, noting that last month was the warmest August on record here.

Swaths of brown grass may be something of an eyesore to those who prefer a lush green lawn, but it’s a matter of life and death for insects that live in grass, and the birds that eat those insects. Streams that have gone way down or dried up completely are also bad news for many species, said Primack, who was quoted in an August 27 Boston Globe article about the drought’s effects on wildlife.

“They’re going to die—there’s no place for the fish and aquatic insects to live,” he said. “A lot of aquatic animals are in trouble.” Making things worse is that nutrients in the remaining water become more concentrated, leading to algal blooms and lack of oxygen in the water.

Plant life has changed as well, said Primack as he showed photos of the banks of Walden Pond where the water has receded. Alders that used to be on the water’s edge have died, while shrubs, grasses and wildflowers such as purple gerardia and golden hyssop have grown in the soil that was formerly underwater. They, too, will perish when the water level rises again, said Primack, who has studied the effects of warming climate on New England plants, birds and butterflies for the last 14 years and is the author of .”

Farmers are certainly feeling the effects of the drought. Corn, pumpkins and other crops will die if they aren’t irrigated, and the yield from fruit trees will also be down this fall. Plants and trees that didn’t flower mean trouble for bees and butterflies as well. But not all plants are suffering, Primack said; succulents (relatives of desert plants) such as purslane, knotweed, spurges and sedum are “really common and really huge,” he said. By the same token, Southern magnolias and even fig trees may thrive in a climate that was once too harsh for them.

The biggest losers may be birds, who are usually eating juicy wild berries and crabapples but have little to eat this year. “There are very few birds in forests and fields; they’ve left to find food somewhere else, and migratory birds have left early. It will take many years for bird populations to recover,” Primack said.

Also scarcer due to the dry weather are insects such as mosquitoes, ticks and deer flies, and amphibians such as salamanders that live in vernal pools that dried up earlier than usual. People may have noticed fewer of the nuisance insects and more butterflies and bees congregating in their flower gardens, which (assuming they’ve been watered over the summer) are a target for the hungry insects. One insect that has thrived, however, is the antlion, which build sand traps resembling inverse anthills in sandy areas around dried-up lakebeds.

The rain will return, but New England will see these conditions more and more often, primack said. With temperatures predicted to get 4–6 degrees F. warmer over the next century, “this will be a typical year 80 years from now,” while low-lying coastal areas of South Boston, Somerville and Everett will be underwater, he said

Gardening with less water

In conditions like this, what’s a gardener to do? Lincoln Garden Club member Daniela Caride had some suggestions focusing on “sustainable gardening.” To minimize water usage, she recommended investing in rain barrels, avoiding sprinklers, and watering only at night or early in the morning rather than in the heat of the day.

Options for lawns include simply having a smaller lawn, planting other types of ground cover, or turning your lawn into a wildflower meadow. Mulch (especially leaf mulch, which is cheaper and easier to handle than bark mulch) is good for keeping moisture in the soil and providing shade and shelter for small animals and insects, Caride added.

When planning your garden, “think before you plant,” Caride said. Avoid “thirsty” plants like chameleon, roses and astilbe, which can suck up water even from surrounding plants, and go for more native plants, which are adapted to our climate (thus needing less watering) and offer food and shelter for small animals and insects.

Leave a Reply