Editor’s note: This is a follow-up piece to the “Where Does It All Go?” series published in the Lincoln Squirrel in August 2022. Links can be found at the bottom of this article.

By Alice Waugh

Lincoln is doing its part by recycling and composting diligently, but there’s always room for improvement to meet the state’s ambitious goals for reducing solid waste disposal — trash, recyclables, and everything in between.

The Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection’s 2030 Solid Waste Master Plan released in 2021 calls for reducing disposal statewide by 30% percent (from 5.7 million tons in 2018 to 4 million tons in 2030) by 2030 and sets a long-term goal of achieving a 90 percent reduction in disposal to 570,000 tons by 2050. To this end, MassDEP has been banning more items from the trash and encouraging composting, while recycling sorting facilities are working on reducing contamination and educating consumers about what and what not to recycle.

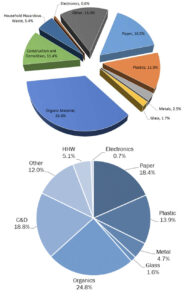

Residential waste by category that was processed by Wheelabrator/WIN Waste Innovations in North Andover in 2019 (top) and 2022.

Trash and what goes into it

There’s a long list of items that are not allowed to go into the trash, including construction and demolition materials (asphalt pavement, brick, concrete, clean gypsum wallboard and wood) as well as tires, large appliances, lead acid batteries, metal, yard waste, and cathode ray tubes in addition to recyclables. In November 2022, that list of banned materials was expanded to include mattresses, textiles, and commercial food from facilities and organizations generating more than one-half ton of those materials per week (down from the limit of one ton per week imposed in 2014)

The largest category of waste sent to municipal waste combustors (a.k.a. MWCs, incinerators, or waste-to-energy plants) is organic material — mostly food waste. However, the share of those organics in the waste stream for WIN Waste Innovations (formerly Wheelabrator) in North Andover, Lincoln’s trash handler, dropped sharply from 35.6% of the waste stream in 2019 to 24.8%, according to the report for 2022. This is at least in part due to the availability of grants through MassDEP’s Sustainable Materials Recovery Program that helps pay for compost bins and implement programs.

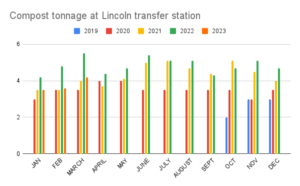

Under an agreement with Black Earth Compost, Lincoln began accepting compost at the transfer station in 2019 (the company also does curbside pickup and lists what is and isn’t compostable). The amounts dropped off each month rose consistently year over year until the first quarter of 2023, when the transfer station accepted 12 tons of compost — down from 14.5 tons in the first quarter of 2022, according to the Department of Public Works.

The state is also working to reduce food waste from small businesses and residents by fostering more development of community and drop-off composting programs as well as efficient models for curbside food waste collection.

Years ago, transfer stations in Lincoln and other towns used to take construction and demolition debris as bulky waste for incineration, but that material is no longer acceptable in the municipal waste stream. Some of it (along with recyclables) was still sneaking into the bulky waste container near the metals container at the transfer station, but since the container became accessible only with the help of a DPW employee, the amount of unacceptable materials has dropped, the DPW reported.

On the other hand, the percentage of construction and demolition debris collected by Waste Innovations in North Andover has increased from 11.4% to 18.8% of the materials total from 2019 to 2022 for reasons that are unclear. The Construction & Demolition Recycling Association and MassDEP provide information on managing debris, including where to dispose of it.

The state monitors the loads sent to MWCs can levy fines on towns that include too many unacceptable items. In the past year, four municipalities — Arlington, Boston, Natick, and Quincy — have been warned though not fined by MassDEP for having recyclable cardboard in their trash, according to MassDEP spokesman Ed Coletta. Cambridge (mattress/box springs) and Watertown (mattresses and tires) were also warned.

Burning vs. burying

Back in the day, most garbage was sent to a landfill or burned in open fires, both of which had (and still have) drawbacks. Like many densely populated parts of the country, Massachusetts began running out of space for landfills, which also released greenhouse gases such as methane into the atmosphere, as well as other pollutants into the ground and water. MassDEP has closed all unlined landfills and requires the remaining few to close when they reach capacity. Most of the state’s trash now goes to MWCs via transfer stations or private haulers. Today it has only 16 active landfills, and three of those accept only ash and other waste left over from MWC combustion.

Those facilities are about half as energy-efficient as modern natural gas power plants, with an electrical efficiency of approximately 24% vs. 50%, Coletta said. “The electrical efficiency of a MWC is lower primarily due to the fuel type (i.e., solid waste) that has less energy content (for example, less carbon and greater water content) than natural gas,” he explained. Like landfills, MWCs emit pollutants, although they are regulated by MassDEP and the federal government to ensure they do not “pose significant risks to public health or the environment,” though the agency notes that it’s not possible to completely eliminate emissions from combustion.

As alternatives to incineration for nonrecyclable plastic, gasification and pyrolysis (heating in the absence of oxygen to produce hydrocarbons to make more plastic or fuel oil) are being explored, but there are challenging costs and drawbacks. Pyrolysis still produces carbon dioxide and other atmospheric pollutants, and it is energy-intensive, sometimes requiring even more energy than it yields. The mixture of different types of plastic and contaminants being pyrolyzed is also a problem.

“There’s too many types,” said Jen Dell, a chemical engineer, in a 2022 Chemical Engineering News article. “There are too many additives. You can’t recycle them all together, and separating them out defies the second law of thermodynamics. It is just impossible to reorder all these plastics once they’ve been put into a curbside bin.” Finally, some also point out that pyrolysis does nothing to reduce dependence on plastics, since it only produces more plastic.

For cities and towns today, “the question of whether landfills or municipal waste combustion facilities is a complicated question – each has its pros and cons. Our focus in our 2030 Solid Waste Master Plan is to reduce the amount of waste that is disposed overall, whether it is disposed of at an in-state landfill, in-state combustion facility, or out-of-state landfill,” Coletta said.

In a welcome twist that was unforeseen when polluting landfills were filling up and closing, some capped landfills such as Lincoln’s are now being turned over as sites for solar panels. Lincoln has hired a firm to install a solar installation atop the landfill across from the transfer station that could eventually generate enough electricity to power all town-owned buildings excluding the schools.

Recycling

As always, the best approach to reducing overall waste is a combination of the “five Rs”: Refuse, Reduce, Reuse, Recycle, and Rot. (“Refuse” means saying no to disposable single-use plastic, coffee cups, utensils, straws, shopping bags, food packaging, and anything else you could replace with a reusable or compostable option.) Even though it’s listed as #4, recycling — in particular, single-stream recycling — is probably the most familiar strategy.

As noted in the Lincoln Squirrel last year, Lincoln’s recycling rate (the proportion of recyclables diverted from the trash) since 2012 has averaged about 40%, which is slightly better than the statewide average of 33% but well below world-leading cities including San Francisco, Seattle, and Los Angeles in the U.S., which recycle or divert about 80 percent of their waste from landfills and MWCs.

Lincoln sends its single-stream recycling to Waste Management in Billerica for sorting and sale. A group of residents from the Green Energy Committee and Mothers Out Front visited the facility in February 2023 to learn how the process works and made this two-minute video. But they still had some unanswered questions, so the Lincoln Squirrel talked to Chris Lucarelle, Waste Management’s Area Director for Recycling Operations. Here are his replies:

Is it correct to say that anything stamped with #1, #2 or #5 is recyclable?

We prefer that we say “plastic bottles, jars, tubs and lids” rather than numbers.

Can other household items made of plastic be recycled along with cans, bottles, etc.? For example, plastic toys/chairs/buckets, reusable plastic kitchenware?

Not kitchenware, but we do separate items like buckets and crates that are bales and sold as a bulky rigid plastic grade.

What happens to nonrecyclable plastic? Can it be sold for pyrolysis or some other use, or does it all get sent to the incinerator?

We are working on solutions for those miscellaneous plastics but we’re not quite there yet.

How big a problem is contamination of recyclable plastics with nonrecyclable types or other things?

Because we sort all of our plastics optically, we are able to make bales of just PET or HDPE [#1 and #2] without contaminating the batch. To keep plastics out of the paper when sorting, we are now automating our paper lines with optical sorters to extract any plastic that found its way into the stream. Sometimes it’s usable flattened containers that can be recovered and sometimes it’s film and pouches that ends up with the residue.

Do you expect to be able to accept black plastic as a recyclable material any time soon?

Some of our facilities have the technology today to recover black plastic, but not all facilities yet.

Aside from “tanglers” (plastic bags, wire, rope, hoses, etc.) that jam the machines, what do you often see in the recycling stream that should not be there?

Small camping propane tanks and lithium ion batteries, both of which are a fire hazard.

What about small metal household items other than cans such as old saucepans, metal pipes, tools, or other small hardware?

This type of scrap metal tends to jam in our equipment or risks injury to our workers. Scrap metal should not be placed in a curbside bin.

Are empty plastic medicine bottles considered trash?

Yes — plastics smaller than two inches in any dimension should not go in the recycling bin. This includes loose plastic bottle caps, which tend to fall through the equipment at recycling processing facilities (put caps back on bottles before recycling).

I hear that small Fancy Feast-type cat food cans should not be part of single stream recycling – why?

They are often lined with plastic.

Is shredded paper OK?

Many of our MRFs [materials recovery facilities] accept shredded paper from commercial sources as an independent stream. When it is placed in the single-stream bins, it ends up contaminating the glass.

(Belinda Gingrich, who was part of the tour by Lincolnites, also noted that shredded paper and small scraps “fly about like confetti. Any paper smaller than two inches on a side will most likely get lost in the system and end up in the trash containers that reside under the conveyor belts.”)

More information about recycling:

- Recyclopedia (created by Recycle Smart MA, a program funded by MassDEP), where you can look up almost anything to find out whether you can put it in your recycling bin. For items that aren’t allowed, the site also suggests other means of disposal, such as Beyond the Bin.

- Recycling 101 from Waste Management, which sorts the recyclables from Lincoln and other area towns

- The Lincoln transfer station

- The “Where does it all go” series in the Lincoln Squirrel from 2022:

Leave a Reply