The Lincoln Public Library archives contain all sorts of historical items, but not all of them are on paper — a quilt that was made for a woman before she sailed off to be a missionary recently came out of the vault to be admired and rewrapped.

The Lincoln Public Library archives contain all sorts of historical items, but not all of them are on paper — a quilt that was made for a woman before she sailed off to be a missionary recently came out of the vault to be admired and rewrapped.

The Flint family, which has lived in Lincoln since the 1600s, donated the quilt to the library some years ago. Three generations of Flints were on hand in the Tarbell Room when the quilt was removed from its box, carefully unfolded on the big table, and refolded with layers of acid-free tissue paper for posterity.

Overseeing the process was Virginia Rundell, Lincoln’s town archivist, who splits her part-time job between the library and working with materials including vital records (births, marriages and deaths) the Town Office Building.

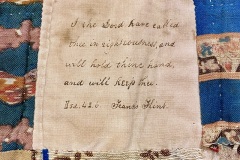

When 26-year-old Mary Susan Rice, an ancestor of the Flints, decided to travel to Persia in 1847 to pursue her missionary vocation, members of the Lincoln Ladies’ Missionary Sewing Circle (part of the First Parish Congregational Church) sewed individual squares for the quilt and added hand-written messages of inspiration and affection, many of which are still legible today. They did this knowing that it would serve as a cherished reminder of her Lincoln home for Rice, who quite possibly would never return, given the dangers of distant travel at the time.

The large quilt (109” x 96”) has an unusual structure, with cutouts at the two bottom corners to allow it to be laid flat on a four-poster bed. It was made of scraps of many types of material but only lightly quilted for “sentimental value rather than hard everyday use,” according to a 1998 article by Tracy Barron of the American Quilt Study Group.

Each of the 82 squares contains a personal note or Bible verse signed by Rice’s numerous friends, family and acquaintances, among them her mother, who penned a heartfelt inscription into the cloth:

Father to Thee

I yield the trust. O bless her with a love

Deeper and purer, stronger far than mine.

Shield her from sin, from sorrow and from pain.

But should thy wisdom deem affliction best,

Let love be mingled with the chastening.

With an unshrinking heart I give her, Lord, to Thee.

Thy will, not mine be done.

(A bit of research revealed that this was not an original composition by Rice’s mother; it appeared at least once before in print. It’s part of “Love’s Offering” published in The Mother’s Magazine in 1840.)

Rice was well qualified to teach at the Fiske Girls’ School in Oroomiah, Persia (now Rezaiyeh, Iran) — she had attended Mt. Holyoke Female Seminary (later Mt. Holyoke College), founded just 10 years before her departure by Mary Lyon, who also contributed a Biblical verse and wish on one of the quilt’s squares.

Rice did in fact return to Lincoln after 22 years in Persia, where she “helped implement progressive ideas about the roe of women in a society where women were not educated and considered second-class citizens,” Barron says. Some of her students even converted to Christianity in “Holyoke-style revivals.” She resumed living in Lincoln and attending Sewing Circle meetings until her death in 1903.

Mary Susan Rice was the sister of Caroline Rice Flint, the great-grandmother of Peggy Flint Weir and Ephraim Flint. Mary and Caroline grew up in the house that still stands at 7 Old Lexington Rd. When Mary returned from Persia, she lived with her sister and brother-in-law Ephraim Flint in the Flint homestead on Lexington Road, still home to three generations of Flints. The quilt was found by Margaret Flint Sr. in the attic of Bertha Chapin, whose mother also grew up in the Flint homestead, according to family members.

Preserving artifacts like the quilt are central to the work of archivists like Rundell. Along with local historians, they’re sometimes called on when older residents are downsizing and looking to dispose of old letters, photos, papers, records and other materials that may have been sitting in attics or basements for decades. Documents that are deemed historically significant are treated so the paper so won’t degrade any further. Sometimes books are unbound and later archivally rebound so they can be digitized, making them available online to researchers anywhere in the world. Much of this work in Lincoln is funded by annual town budget appropriations requested by the Community Preservation Committee (the money comes from property taxes and the state).

Another part of the job is making archival materials more “discoverable” using finding aids for the various collections pertaining to Lincoln buildings, families, events, organizations and photographs. “One of the big goals is to get people engaged with the archives,” Rundell said. “You don’t get this stuff and put it in a vault so it just sits there — you went people to use it.”

Click on an image below for a larger version and caption (photos by Alice Waugh).

What a wonderful story! Congratulations and thank you to the Flint family.

What a wonderful object of history, artistry, and community. Kudos to the Flint family and Town Archivist Virginia Rundell for assuring that it is carefully preserved and—most important—will be accessible for future generations to appreciate. I was amused by the comment that this coverlet was “only lightly quilted for ‘sentimental value rather than hard everyday use,'” In fact, the climate of Rezaiyeh (now Urmia) Iran is pretty much like Lincoln (but without the snow). Mary Susan Rice might have wished for a little more stuffing on those cold Persian nights!

Thanks also to Alice Waugh for covering this occasion so well.