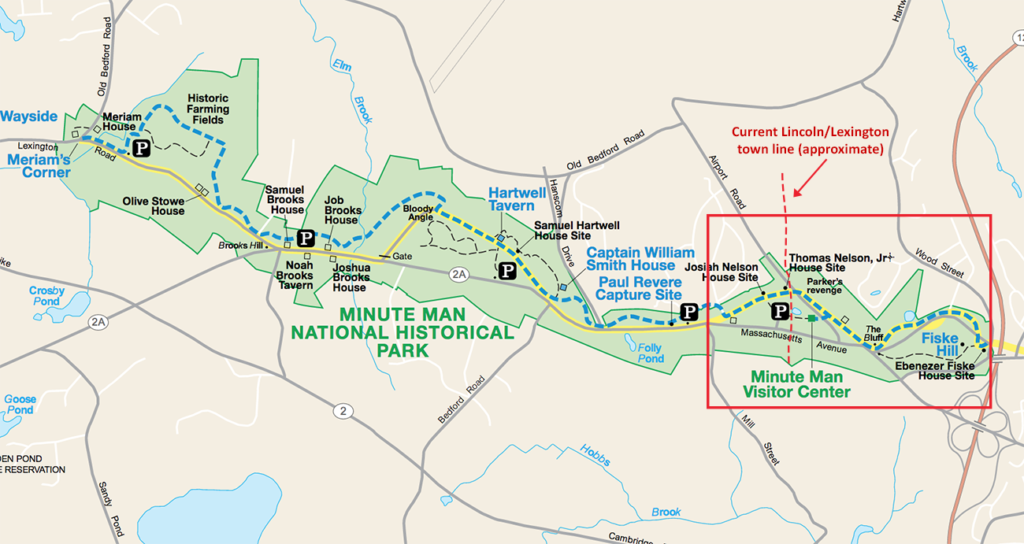

Minute Man National Historic Park. The area in the red box is shown in an expanded view below (click to enlarge).

The Friends of Minute Man National Park have released the final archaeology report on the Parker’s Revenge battle – the April 19, 1775 encounter in which Captain John Parker engaged the British regulars on their march back from Concord through Lincoln to Boston.

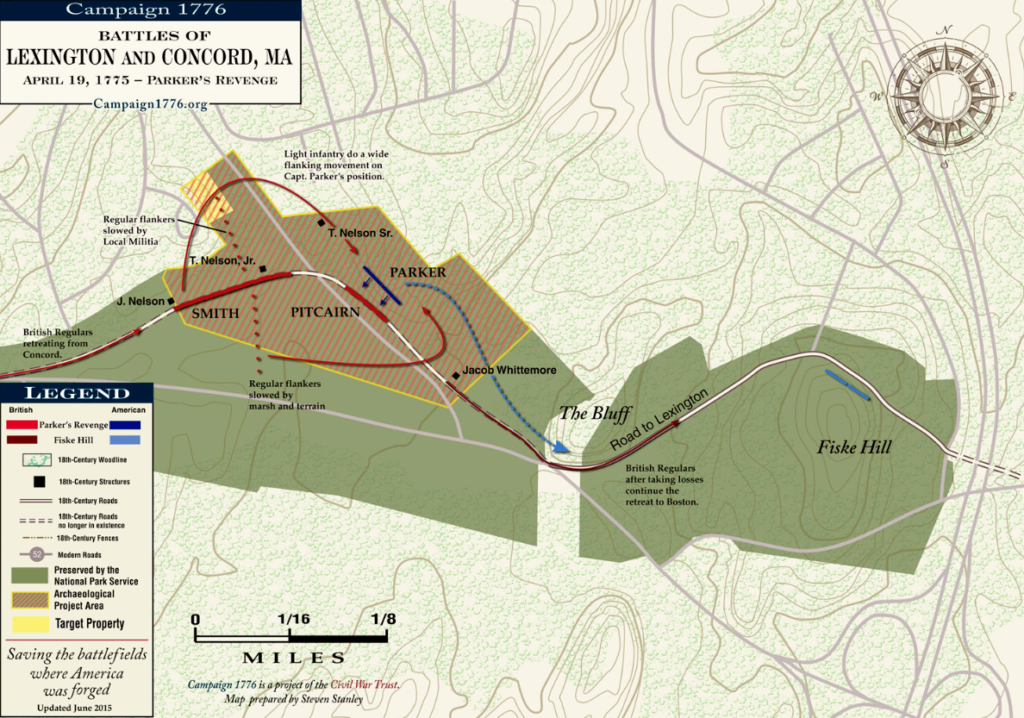

Parker was commander of the Lexington colonial militia that exchanged fire in Lexington on the first morning of the Revolutionary Way. Eight militia were killed (including Parker’s cousin Jonas) and the Americans fled. But that afternoon, colonials ambushed the British at several points during their return march to Boston, including at a sharp bend in the Battle Road in Lincoln now known as the “Bloody Angle.” The Parker’s Revenge skirmish took place further east around the current Lexington/Lincoln town line. (The Bloody Angle fight is memorialized in a painting and document now hanging in the recently renovated basement of Bemis Hall.)

The 320-page report summarizes historical research on the battle, details the full range of technologies deployed in the archaeological research, and describes battle tactics likely utilized by both colonial and British forces. The project findings are especially noteworthy in light of the fact that only one brief witness account the battle has ever been identified by historians.

Twenty-first-century technologies utilized in the research informed formal excavations and 1775 battlefield reconstructions included 3D laser scanning; GPS feature mapping; and geophysical surveys including metallic surveys, ground penetrating radar, magnetic gradient and conductivity/magnetic susceptibility. Taken together, the technologies enabled researchers to locate a farmhouse that figured prominently in the battle terrain, to recreate the actual 1775 battlefield landscape and battlefield features, and even to model exactly what combatants could and could not see at various positions along the battle road.

Artifacts discovered included 29 British and colonial musket balls from the battle. The location and spatial patterning of the musket balls recovered enabled archaeologists to interpret the exact positions where individuals were standing during the battle—and then outline battle tactics most likely deployed.

“Using an integrated approach to interpreting this battlefield enabled us to literally peel back time and expose the artifacts that tell the story of Parker’s Revenge,” said project archaeologist Dr. Meg Watters.

The report indicates that Captain Parker positioned his men at the edge of a wood lot on an elevated slope above the battle road. This particular site had two distinct advantages: it provided a clear view to see the advancing British forces and the landscape featured a number of large boulders and trees that provided cover.

A view shed is an area visible from one specific location in a landscape. Archaeologists ran a computer simulated view shed analysis taken from the perspective of a 5’5”-tall marching British soldier and also from the point of view of a mounted British officer (nine feet above ground). The analysis indicated that the undulating terrain surface, combined with other obstacles, meant the British force could not easily see the position of the Lexington militia until it was in close proximity.