By Maureen Belt

Lincoln resident Rob Stringer has dabbled in art his whole life, even taking art classes to round out his college study of religion and philosophy, but it wasn’t until May 25, 2020 that he used its power to take on racism.

“The day George Floyd died — when he was murdered — I knew I had to do something,” he said.

What that “something” would be did not come to him right away. He had a delicate act to balance. The country was already deeply divided politically and racially, and he wanted his actions to provoke positive reflections of current events, not to be discarded as virtual signaling.

“I am a cis white male who lives a privileged life,” said Stringer, speaking from his transient office, which on this day was the Tack Room restaurant in Lincoln. “But I wanted to do something, and I kept wondering, ‘What can I do that’s authentic?’ I didn’t want to go to protests and then just go about my daily life. I didn’t want to do anything ephemeral. I kept asking myself, ‘What can I do? What can I do?’”

The answer was in his art.

Until George Floyd’s death, drawing was the medium Stringer relied on for expression. But the horrors surrounding George Floyd — whose brutal killing by law enforcement was captured on video and generated a global uprising for racial equity — called for something more dramatic. In an earlier life, Stringer worked in sales, marketing, and product development, so he regularly prepared slide decks using PowerPoint. He subsequently discovered that Google Slides offered broad options in color and shape.

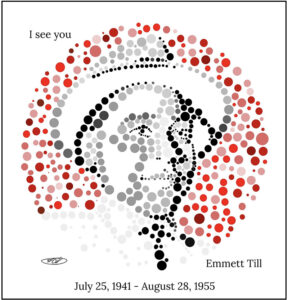

Stringer downloaded another artist’s image of George Floyd, then began overlaying it with colored dots simulating the Ishihara color vision test to create his own portrait. After a bit of trial and error over about five hours, an impactful rounded image of the murder victim appeared, created from various sizes of gray, black and blue dots. The colorblind motif was intentional, as Stringer has red-green colorblindness.

Beneath the portrait, Stringer put Floyd’s dates of birth and death and name in a basic black font. He emailed the digital image to the online printing venue, VistaPrint, which cast it on a 12-inch-by-12-inch canvas. The finished work was so moving that it inspired him to do more. He next used the same formula to portray Breonna Taylor, who was killed by police two months before Floyd.

Stringer soon completed a series of Black people killed by police including Daniel Prude, Crystal Danielle Ragland, and Rayshard Brooks. He then created images of Blacks killed in hate crimes, which include Treyvon Martin, Martin Luther King Jr., and Emmett Till. From there, Stringer’s work evolved to include Native Americans murdered by law enforcement or from hate crimes. Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention indicated that though Indigenous people made up 0.8 percent of the population from 1999 to 2011, they made up 1.9 percent of police killings. His First Nations collection includes images of Sitting Bull, Zachary Bear Heels, and a dedication to missing and murdered Indigenous women.

“I am not running out of subjects,” he acknowledged with disappointment. “My hope is that maybe their family members will see the art and that they find that it’s respectful.”

After so many portraits of murder victims, Stringer changed his course to creating images of minorities who inspire. That line includes U.S. Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland, Rosa Parks, and Ruby Bridges. “I’ve been interested in power dynamics and the dynamics of race for a long time,” he said. “And in the back of my head I was feeling guilty that I was not doing more.”

Stringer didn’t create these images (which he describes more as graphic design than fine art) to make money, so he had no plans to market them, but some people who viewed them asked for prints. VistaPrint charges him $20 for the print, so he sells it for $29 and gives the extra $9 to a nonprofit — specifically, the METCO program.

Stringer’s most popular images are of Breonna Taylor and Emmett Till. He is sold out of his prints of Jean McGuire, the first Black woman elected to the Boston School Committee, a founder of the METCO program and at, 92 years old, a living icon of the local educational community.

“It’s affirming to me that I was able to create something that impacts other people,” he said. “It makes me want to continue. These pieces spark conversation and they spark thought and they change people’s minds, and you can’t ask for more than that.”

View Stringer’s online “I See You” gallery here.

Leave a Reply