By David P. Braun

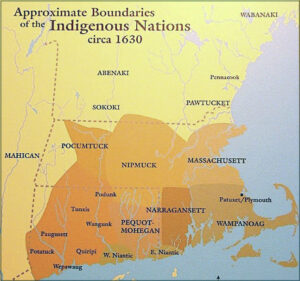

When people ask, “who were the first inhabitants of Lincoln,” they often mean, “what tribe lived here?” The short answer is, probably Massachuset.

But as best we can tell, most Native American “tribes” were somewhat fluid. They did not have rigid boundaries or a concept of land as property in the way that the European invaders did. With some exceptions, they were more like loose confederacies of local communities that sometimes acted together as larger groups. They had territories based upon their traditional uses of the landscape, their shared history, and their shared history of alliances and disputes with neighboring groups. They spoke related, mutually intelligible Algonquian languages and were descendants of Algonquian-speaking communities that had lived and evolved together for thousands of years.

The exact tribes known from the historic record may not have had that much antiquity. Social relationships and identities likely evolved over those thousands of years, as lifeways changed and as populations grew and shifted over time. But the incorporation of agriculture into their lifeways starting around 1000 A.D. likely brought considerable changes. Populations grew faster, and areas with good soils for farming would have become valuable resources.

Occasionally, where the edges of tribal territories met or overlapped, the communities would have worked out rules for sharing. There is a lake in Webster, Massachusetts, famously named (or at least so recorded), as

“Chargoggagoggmanchauggagoggchaubunagungamaugg”

If my memory serves, this native name is usually translated literally as something like “you fish on your side of the lake, we fish on our side of the lake, and nobody fishes in the middle.” However, Algonquian languages are very figurative. The local communities might have thought of the lake simply as “Border Treaty Lake.”

Places such as Lincoln, which is mostly upland terrain, may have been part of some native communities’ identities and hunting territories before Europeans arrived, but not the site of winter or even seasonal villages. That was not how the indigenous communities lived. Instead, the adjacent Sudbury/Concord/Merrimack River valley and its wetlands would have been far more important as dwelling places. The rivers were avenues of travel and sources of food, and the floodplains would have provided productive farmland near to their villages.

Places such as Lincoln, which is mostly upland terrain, may have been part of some native communities’ identities and hunting territories before Europeans arrived, but not the site of winter or even seasonal villages. That was not how the indigenous communities lived. Instead, the adjacent Sudbury/Concord/Merrimack River valley and its wetlands would have been far more important as dwelling places. The rivers were avenues of travel and sources of food, and the floodplains would have provided productive farmland near to their villages.

The arrival of the Europeans in the early 1600s and the fatal diseases they brought caused havoc, disrupting the indigenous peoples’ lives, locations, and connections with each other. Many communities became mixtures of local natives and refugees from neighboring areas that had suffered worse. And the written records we have of these communities post-date the start of that havoc. They do not necessarily record how the people lived beforehand. The historic records, biased though they may be (after all, who wrote them? Not the natives…), suggest that the natives did their best to maintain their sense of identity and their identification with their traditional home landscapes. But the European diseases killed their elders fast. As the native communities lost their elders (with their unwritten stores of history and traditional knowledge), they lost much of their collective cultural memories.

It is wrenching to think of the thousands of years of tradition and knowledge that were lost with the erasure of these communities.

For those who wish to read more, I recommend Charles Mann’s book, 1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created (2011). It is grim reading but also important and fascinating. Also valuable is Nathaniel Philbrick’s book, Mayflower (2006). This also is grim and specific to southeastern New England, but an excellent treatment of how the natives and early European settlers in the Massachusetts Bay area perceived and treated each other.

Addendum — After this story was published, town historian Jack MacLean offered this additional information abut the map:

The map here shows Massachuset territories extending further north than was the case at the time of contact. Along the coast, lands associated with the Pawtucket Confederation extended down to Charlestown, which was purchased from Pawtucket leaders. Boston (Shawmut) was associated with the Massachuset, with the Charles River providing a divide. Watertown and Cambridge south of the river were also Massachuset. However, Lincoln’s primary parent community of Concord was purchased from local leaders (Tahattawan) and from Squaw Sachem, along with her second husband, who lived at Mistick (Medford). Squaw Sachem had succeeded her first husband (Nanepashemet) as the leader of the Pawtucket Confederation. While Concord was formally seen as being under Squaw Sachem and the Pawtucket Confederation, the close proximity of the two “tribal” groups in this area indeed suggests much fluidity and interconnectedness.

David, it should be noted, is the coauthor with his mother of The First Peoples of the Northeast.

“Lincoln’s History” is an occasional column by members of the Lincoln Historical Society.

The map here shows Massachuset territories extending further north than was the case at the time of contact. Along the coast, lands associated with the Pawtucket Confederation extended down to Charlestown, which was purchased from Pawtucket leaders. Boston (Shawmut) was associated with the Massachuset, with the Charles River providing a divide. Watertown and Cambridge south of the river were also Massachuset. However, Lincoln’s primary parent community of Concord was purchased from local leaders (Tahattawan) and from Squaw Sachem, along with her second husband, who lived at Mistick (Medford). Squaw Sachem had succeeded her first husband (Nanepashemet) as the leader of the Pawtucket Confederation. While Concord was formally seen as being under Squaw Sachem and the Pawtucket Confederation, the close proximity of the two “tribal” groups in this area indeed suggests much fluidity and interconnectedness.

David, it should be noted, is the coauthor with his mother of The First Peoples of the Northeast.

Jack MacLean, Lincoln Town Historian, is the author of “A Rich Harvest”-a comprehensive, and highly readable history of the town of Lincoln, available through the Lincoln Historical Society and at Something Special.

Sara Mattes

And just because, despite the grim horrors, Indigenous peoples did not fade into oblivion after the 17th century, and indeed, are more vibrant than ever in the present day, I recommend “The Heartbeat of Wounded Knee” by David Treuer which continues the story.