Editor’s note: This is the first article in a new series called “Lincoln’s History” written by the Lincoln Historical Society.

Editor’s note: This is the first article in a new series called “Lincoln’s History” written by the Lincoln Historical Society.

By Don Hafner

Black History Month is a time to reflect upon stories of Lincoln’s own history of slavery. Here is one such story.

Against all odds, Violet Thayer of Lincoln was a successful businesswoman. When she died in 1813, she was in her seventies and had never married. Violet’s mother was still alive, but she was blind and incapable of managing her late daughter’s affairs, so John Hartwell, proprietor of the Hartwell tavern, handled Violet’s estate.

The probate inventory of Violet’s property included what we might expect of a successful seamstress — two calico gowns, one cambric gown, four short gowns, twenty yards of shirting fabric, thimbles, yarn. In all, the estate was valued at $114. Three more items showed Violet’s success and savvy as a businesswoman. She had $30 in cash, as well as two loans she had made that paid her interest—one to Bulkley Adams for $20 and the other to Samuel Hartwell for $27.

During the seven weeks of Violet’s terminal illness, she was cared for by John and Hepzibah Hartwell. John Hartwell claimed a third of Violet’s estate for his expenses in boarding her during these weeks, but that still left something for her aged and blind mother.

Violet Thayer’s success did not come easily. She had been born into slavery and had been enslaved “from infancy” in the households of Ephraim and Elizabeth Hartwell and then John and Hepzibah Hartwell. Yet by the time of her death, Violet had earned enough money on her own to make loans to two of Lincoln’s prominent citizens. Quite likely, these “loans” were Violet’s shrewd equivalent of a savings account that paid interest at a time when Lincoln had no banks.

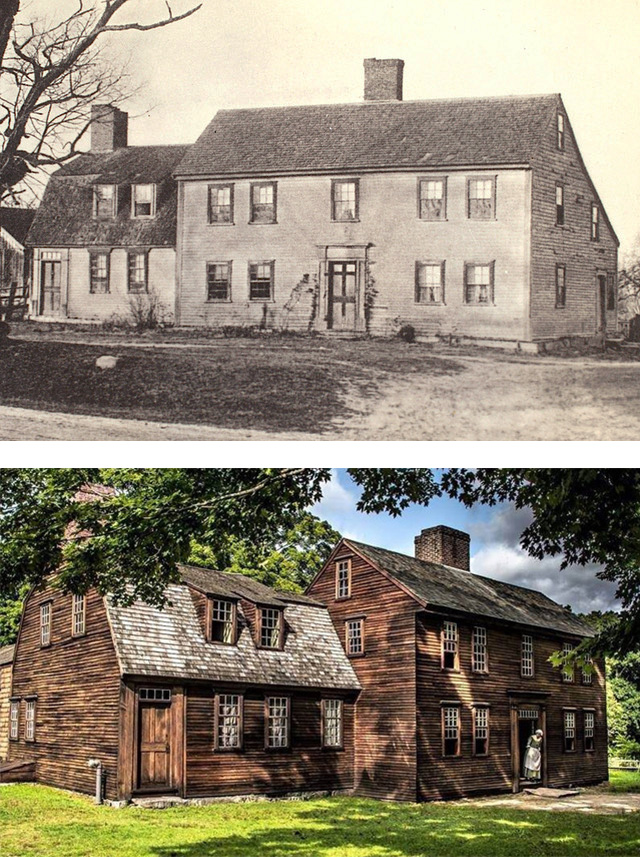

Hartwell Tavern in 1904 and in modern times. The house (now part of Minute Man National Historical Park) was originally built as a home for Ephraim Hartwell and his newlywed wife Elizabeth in 1733.

Also against the odds, the Hartwells attempted to hold Violet in bondage even after the state Supreme Judicial Court pronounced in 1783 that the court was “fully of the opinion that perpetual servitude can no longer be tolerated in our government.” Essentially, the court gave every “servant for life” in Massachusetts the opportunity to simply walk away from their owners, including the dozen or so slave owners in Lincoln. Yet five years later, when Ephraim Hartwell made out his will in 1788, he included this clause: “I give unto Elizabeth Hartwell my beloved wife … my Negro woman, named Violet for her own service & disposal.”

Ephraim Hartwell died in 1793, and the probate inventory of his estate did not include any mention of Violet among his “property.” Perhaps she had challenged her enslavement; perhaps she had simply been released by the Hartwells. Either way, when freedom finally came to her, Violet Thayer made her own path in the world—and quite successfully.

For more on slavery in Lincoln, see A Rich Harvest by John C. MacLean, especially pages 216-221. Copies of are available from the Lincoln Historical Society.

Addendum (March 1, 2021):

Did you know that the end of slavery in Massachusetts was complicated, and there was not a single action or case that ended it. Although in the 1790 census no individuals within Massachusetts were identified as slaves, Hartwell’s ongoing treatment of Violet as a slave two years earlier was not unique and not illegal.

In 1781 there were two important lower-court cases brought by slaves Mum Bett and Quock Walker that resulted in their being declared free. Walker had been owned by Nathaniel Jennison, and other charges developed out of the original case. One was Commonwealth v. Jennison, which related to an incident where Jennison had beaten Walker. In 1783 it had gone to the Supreme Judicial Court, and Jennison was found guilty and fined forty shillings.

Chief Justice William Cushing argued the view that based upon language in the 1780 Massachusetts Constitution (an issue earlier argued in the Mum Bett case), Cushing was “fully of the opinion that perpetual servitude can no longer be tolerated in our government.”

Although highly suggestive, those statements were not part of the formal decision of the court, which was dealing with a narrower issue of assault and battery—so slavery legally continued (including with the Hartwells), but it now became clear that the SJC would not uphold it.

For those interested in research into Massachusetts slavery, a general article I wrote some time back for the New England Historic Genealogical Society includes Lincoln references and is available here.

Jack MacLean

Lincoln Town Historian

Thank you, Don, for reminding us of these important human narratives connected to our town.

fascinating, Don. Well done. And for me, timely! Jeanne Bracken

Really interesting article – thanks Don.

Thank you! This is very interesting to think this happened here in Lincoln!