By Donald Hafner

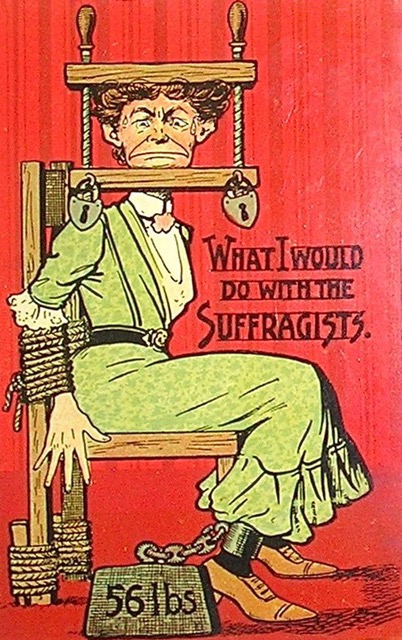

In November 1915, the men of Massachusetts trekked to the polls to decide whether the word “male” should be removed from the state’s qualifications for voting. The Massachusetts Woman Suffrage Association in mid-October had staged a pro-suffrage parade in downtown Boston, with 15,000 marchers and 30 bands, urging a “Yes” vote. A parade of 15,000. Yet according to the Massachusetts Anti-Suffrage Committee, what men should do was deliver “not merely a defeat for woman suffrage, but a defeat so overwhelming that the question will not rise again at least in this generation.”

The men of the town of Lincoln in 1915 took the advice and voted against suffrage for women, 143 to 66 — an even larger rejection than the overall vote in Massachusetts. The Anti-Suffrage Committee asserted that most women did not, in fact, want the right to vote. Given the opportunity, women seemingly ignored it.

In 1879, when women in Massachusetts had been granted the vote for members of their local school committees, fewer than 5% of eligible Massachusetts women registered to vote, and only 2% ever voted. In Lincoln, three women promptly registered to vote, but only one went to the polls.

Women argued that the right to vote for male school board members (only men could hold public office) was too trivial for the bother. Yet in 1895, when Massachusetts women were allowed to vote in a referendum granting women the vote for all local offices, only 7% of eligible women in the state registered to vote and only 4% went to the polls. The 1895 referendum was overwhelmingly defeated by men. In Lincoln, only five women were registered to vote in the referendum, and only three cast ballots — all “Yes” votes.

Women argued that the right to vote for male school board members (only men could hold public office) was too trivial for the bother. Yet in 1895, when Massachusetts women were allowed to vote in a referendum granting women the vote for all local offices, only 7% of eligible women in the state registered to vote and only 4% went to the polls. The 1895 referendum was overwhelmingly defeated by men. In Lincoln, only five women were registered to vote in the referendum, and only three cast ballots — all “Yes” votes.

At the turn of the 20th century, more women in Lincoln registered to vote, perhaps from interest in the local school committee, perhaps just to make a point. Still, by 1919, there were 285 Lincoln women eligible to vote, yet only 40 had registered.

Then on August 28, 1920 — ten days after ratification of the 19th Amendment — 71 Lincoln women flocked to the town clerk’s office to register for their first Presidential election. Impressive, but still only 25% of those women eligible. The anti-suffrage message — that the woman’s place was in the home, not in politics — still had a powerful grip.

On the centennial of the 19th Amendment, one hundred years of slow progress — and more to come.

* * *

Donald Hafner is a member of the board of the Lincoln Historical Society and drum major for the Lincoln Minute Men. He is a retired professor of political science who loves exploring the rich history of the town of Lincoln.

”My Turn” is a forum for Lincoln residents to offer their views on any subject of interest to other Lincolnites. Submissions must be signed with the writer’s name and street address and sent via email to lincolnsquirrelnews@gmail.com. Items will be edited for punctuation, spelling, style, etc., and will be published at the discretion of the editor. Submissions containing personal attacks, errors of fact, or other inappropriate material will not be published.

Ok, now do the percentage of eligible men who voted.

That’s the spirit! In Lincoln for the 1915 referendum, it was probably about 70% of those men eligible to vote. Nationally, the percentage of women voting did not equal the percentage of men voting until the Presidential election of 1980.

DLH

It is still, and always has been, very difficult to go against the the tribe… the majority…even if the majority is wrong… as history frequently proves..

Thank you Don. This was a fun read and a wonderful piece of our local history.

RAH