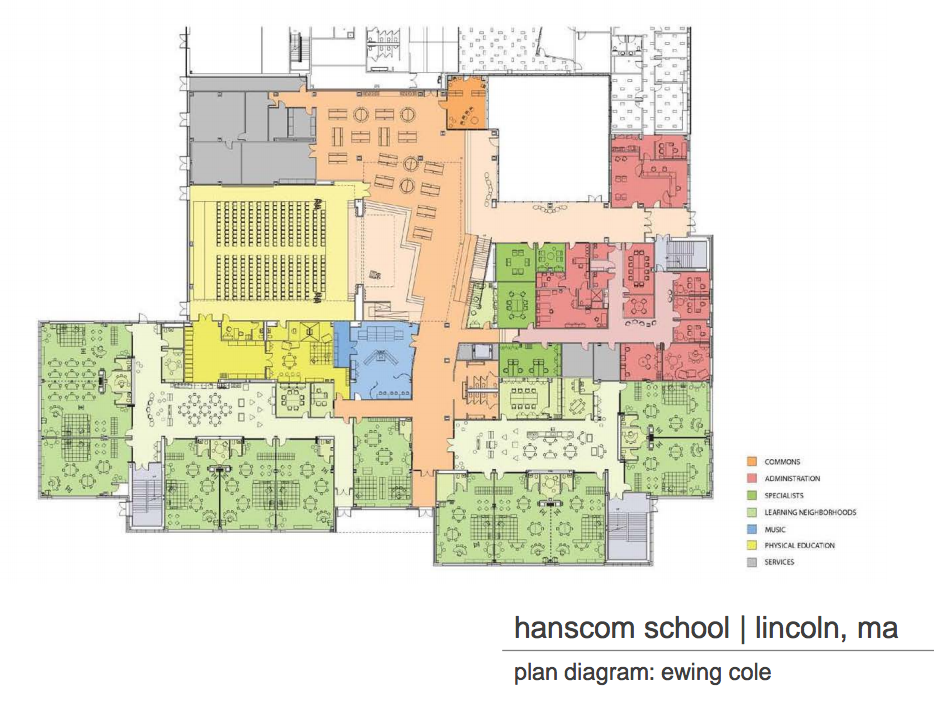

A 2014 drawing of the new Hanscom Middle School calling for “neighborhoods” of classrooms (click to enlarge).

Architects and Superintendent of Schools Rebecca McFall explained how the design elements of a school building can help realize an educational vision for its students at an October 17 School Building Committee workshop.

The building’s design should reflect the educational vision and strategic priorities as approved by the School Committee this year, said McFall, who first outlined the school’s educational needs in a renovated or new building in 2014.

“Educational environments are changing,” said architect Keith Fallon, executive vice president of EwingCole, one of the two firms hired by the SBC. Elementary and middle schools today are designed to support different ways for students to gather and work together. This means flexible spaces of various sizes in addition to the basic classroom so students can be easily taught in groups as small as three or four and as large as an entire grade.

Currently in many parts of the Lincoln School, individuals and small groups who want to work independently during a class must do so in the corridor. “It’s not that the work doesn’t happen, but the spaces could enhance that and increase the impact of the work we’re trying to do,” McFall said.

Many schools illustrated in slides by the EwingCole architects have several classrooms around a central hub rather than the traditional double-loaded corridors, as well as lots of natural light and “maker spaces” throughout. This approach maximizes teaching time by minimizing transitions from one place to another.

Larger common areas for art, music and performances can be centrally located and can even be transparent, such as the art room at the new Hanscom Middle School (HMS), which a number of residents have toured in recent months. Smaller spaces that are more private can also be carved out in a school design characterized by flexibility and ease of modification. “It’s about creating a wide range of educational experience,” McFall said.

Since the new HMS opened in the fall of 2016, students have benefited from the opportunities for student and staff collaboration that the building’s design offers. “They’re able to think about what the learning experience is and what the appropriate space for that might be, [and] they have to talk about who’s using [the common spaces] for what purpose,” McFall said. As a result, “the building has been a true catalyst for changing instruction.”

The ideal school design would also feature seamless technology infrastructure (such as places where students can plug in their own devices to work collaboratively), and a connection to the community and the environment. One of the questions the school’s design must address is “to what extent the life of the school and the life of the community should intersect?” Fallon said.

“We see the schools as an integral part of the community and a necessity for the community,” McFall said. “We’d be open to community events as much as we can.”

Another design question that impacts education is how to integrate sustainability into the curriculum, Fallon said. Seeing and measuring recycling in a new cafeteria and kitchen are natural teaching tools that aren’t available today, with cramped food service facilities without dishwashers where disposable utensils and uneaten food must be thrown out, McFall noted.

Sustainability will also be an important factor in the surrounding landscape design as well as environmental efficiencies in the building itself. Consequently, a single kitchen, cafeteria and food storage area will “absolutely” be part of the design, Fallon said. (Earlier discussions had included the possibility of two separate cafeterias for different age groups.)

In addition to residents, teachers and architects, students are getting the chance to offer their ideas for the school. Groups of students were asked to illustrate their ideas on mural-size paper the previous week and came up with some very creative ideas, including a whale pool, a water slide into the library, and a tree house that could be accessed via zipline from the computer room.

Leave a Reply